Reactions to the death of Stephen Hawking reveal a lot about the psychology of giving. Within hours of the news, the Motor Neurone Disease (MND) Association website collapsed under a wave of public donations – a remarkable demonstration that immediacy in perceptions of need is one of the most powerful triggers to give. We see its power in the ever-increasing annual amounts raised by the media-based Comic Relief appeals. We see it in how real-time global media coverage of humanitarian disasters prompts public generosity.

Crowd-funding is a special case of individual citizens discovering for themselves the huge power of using direct person-to-person web-based appeals to ‘go fund me’ for their individual concerns. When coupled with social and sometimes national media, not to mention tech gimmicks such as real-time targets and progress monitoring, the power of the direct appeal is proving staggering. A formidable example was the J.J.Watts’ campaign to raise funds for Houston Flood Relief.

Does all this suggest that we still haven’t plumbed the real depth of the public’s willingness to give? This would be contrary to the evidence of giving surveys which consistently indicate that giving to charity as a proportion of public spending is virtually unchanged over time.[i] Do these new technology-enabled examples mean society’s potential for compassion and giving to others may be much greater than we think?

Thanks to advancing ICT, immediacy is an increasing feature of global awareness and fundraising. Mass communications techniques are proving a powerful fundraising tool. For Comic Relief the additional inclusion of celebrity presenters in immediate, often heart-breaking appeals from the field has proved monumentally successful in prompting people to give. Stephen Hawking’s celebrity status is no doubt a factor in changing perceptions of disability and the recent surge in donations to the MND Association. He made popular appearances on TV in The Simpsons, featured in Star Trek and The Big Bang Theory and his life was dramatised in the film The Theory of Everything.

But there has been a challenging backlash in these cases too where information value has become mingled with celebrity and entertainment value. Comic Relief has been accused of ‘poverty tourism’ campaigns and ‘poverty porn’. People with disabilities have fought back against the portrayal of Hawking and others as ‘inspirational’ for being high achievers because they are disabled, and not because of what they have done. As one commentator wrote ‘Don’t call me an inspiration. There’s nothing brave or strong about it. I exist. My strength and courage comes from what I do. Not what I am.’

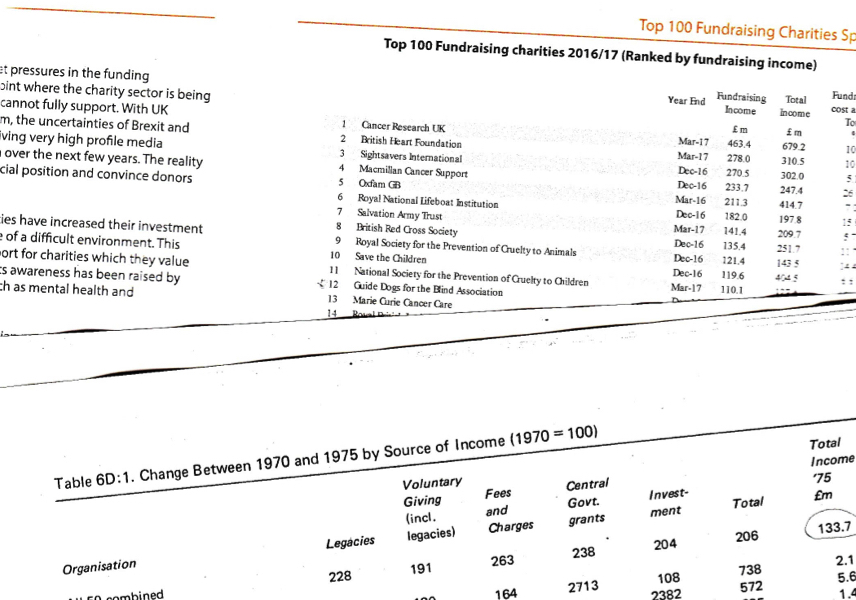

The rights of disabled people have changed radically since the introduction of the 1970 Chronically Sick & Disabled Persons Act. The position of disability causes and charities has changed dramatically alongside this. While 10 of the top 50 fundraising charities in 1975 were dedicated to disability, today there are just 4 in the Top 50. The fastest-growing charities in the early ‘70s included Cheshire Homes (Leonard Cheshire Disability), RNIB, and the Spastics Society (Scope). Disability Rights was founded in 1977 to shift the focus to rights to independent living and entitlement to benefits and services.

It seems that changing images from dependence to empowerment do indeed make public fundraising harder. A £17 million drop in donations to Sports Relief’ on the night’ this year followed the replacement of celebrity TV presenters by users and beneficiaries – apparently fulfilling the prophecy of its CEO that this was a risky strategy, and that celebrities are a sure bet when it comes to bringing in funding.

Donations to Sports Relief may have been at least in part suppressed by recent revelations of sexual misbehaviour amongst some staff in international aid charities. But there is a tricky basket of issues to untangle. Levels of giving to charity are often used as a barometer for measuring compassion and generosity in society. But is the compassion aroused by immediate and emotive images of need, flavoured with celebrity, skin-deep? The public reality is that we will see real cuts in spending on disability benefits of £1.2 billion by end of the term of this parliament, £295 million per year on average.

The growth of the Trussell Trust’s network of food banks is furthr ongoing evidence that charities today still have a crucial job in providing for the immediate relief of need. But a progressive welfare society is one where compassion is measured through real tangible social change in equal opportunities and the lived experience of those in greater need. Many charities feel under an imperative to use techniques which raise as much money from the general public as possible, so that they can provide and even improve services, particularly in a world where governments believe philanthropy can replace public welfare. It’s Catch 22 if the attitudes and perceptions which prompt charitable giving hold back real social improvement.

[i] Cowley, E., MacKenzie, T., Pharoah, C. and Smith, S. (2011) The new state of donation: Three decades of household giving to charity, CGAP/CMPO